100 years of Korean cinema: part three - the Korean New Wave

In the last installment of our Korean Cinema series, we covered the heavy censorship of Korean films during the 1970s and 1980s by a right-wing government. We saw how the influx of money-hungry investors and Hollywood influence scarred Korean cinema. Not only did the quality of films produced in Korea plummet, but there was also very little space for social commentary and films that portrayed the real existence of Koreans. Politically-charged content was rare, in many cases struck down by the government before it could even exist.

In the 1990s, filmmakers were afforded more freedom. A slackening of brutal censorship laws led to a fast increase in the number of independent film studios producing interesting, artful cinema. This was the birth of the Korean New Wave.

In the late 1980s, Korean society was freed from the shackles of a two-decade-long dictatorship. This was catalyzed by The Burger King Effect - American influence began to flood Seoul and proliferate throughout the country. People were enjoying more freedom and financial autonomy than ever before. However, a string of corruption scandals in the government and beyond created growing resentment towards the politicians and other notable figures, leaving a taste of bitter distrust in the mouths of many despite the country’s newfound economic success.

The Host (2006)

Moreover, it was becoming clear to many that the proliferation of American culture in Seoul and beyond was rooted firmly in American neo-imperialism and that success would remain out of reach for many. This period of rapid economic growth is known as the “miracle of the Han River.” But the riches built by the work of many were only ever going to be reaped by a small few. People began to sweat under the ever-growing pressures of the modern world. A shadow of Korea’s turbulent years of protest in the 70s and 80s remained close at hand. This was the beginning of yet another decade of unrest.

Corruption within the government was all too common in Korea. It had plagued the country for decades and showed no signs of dissipating even as Korea moved into the modern world. Chun Doo-hwan was Korea’s military dictator serving from 1980 to 1987. In 1982, his relatives were involved in a financial fraud of over 700 billion won, and faced charges of corruption, tax evasion and embezzlement. August 1983 saw the Myungsung Group scandal, where bank personnel and the Minister of Transportation were arrested for their involvement in large-scale private bills that nearly brought Seoul’s financial markets to a halt.

Similar dishonesty and fraudulence crept up on the 1990s, too. On 1 November 1995, former president Roh Tae-woo was investigated by the Supreme Prosecutors’ Office on bribery charges and was accused of having accepted over 200 billion won in bribes from conglomerates. On 2 December 1995, Chun Doo-hwan was investigated for high treason regarding the coup by which he took power and the Gwangju Uprising of 1980. After a drawn-out hearing process, Roh was sentenced to 22 years imprisonment and Chun received the death sentence. But, this result proved to be no more than a mirage. Not only were both sentences drastically reduced in April 1997, but the two former leaders were specially pardoned on 22 December 1997 by the Kim Dae-jung government. Both Roh Tae-woo and Chun Doo-hwan were sentenced for crimes they committed during office, but the subsequent pardoning made it clear to the public that illicit and illegal actions taken by authority figures would not be dealt with appropriately. People were demoralized. If nothing happened when powerful officials committed serious crimes, how could they trust their government?

Under this gloomy cloud of distrust in authority, Korean cinema surprisingly began to find its footing. The industry began to transform and move in a positive direction around the start of the 1990s, moving away from the censorship laws that had suffocated artistic pursuits. The Korean film market was opened to Hollywood distribution companies in 1988, and the Film Promotion Law of 1996 made it easier for smaller, independent companies to produce films. This led to the rise of production companies owned by young producers who could not afford to produce films before under stricter rules. By 1996, most restrictions to filmmaking had been abolished. The Public Performance Ethics Committee, however, was still in operation and blocked films that had strong sexual content or were mocking in tone towards the government. Nonetheless, in October of the same year, Korea’s Constitutional court ruled that governmental pre-censorship of films was in violation of the constitution, and films ended up being rated by a civilian board but were not censored pre-release. This weakening of censorship laws was a crucial turning point for directors, who were now free to explore more socially-relevant content in their films. This contributed heavily to the emergence of the New Wave films that told stories free of censorship-led persuasion of content.

The Day A Pig Fell Into A Well (1996)

From the end of the 1980s, films telling the stories of the social realities of Korean citizens were finally produced en masse for the first time. Hong Sang Soo’s The Day A Pig Fell Into A Well (1996) is an excellent example of exploring the lives of four young adults as they learn to understand the freedoms and pitfalls of modern life. Though some limited drama lies in the intertwining of the lives of these characters, the film mainly follows their everyday lives, portraying everything from the ordinary, to even the mundane.

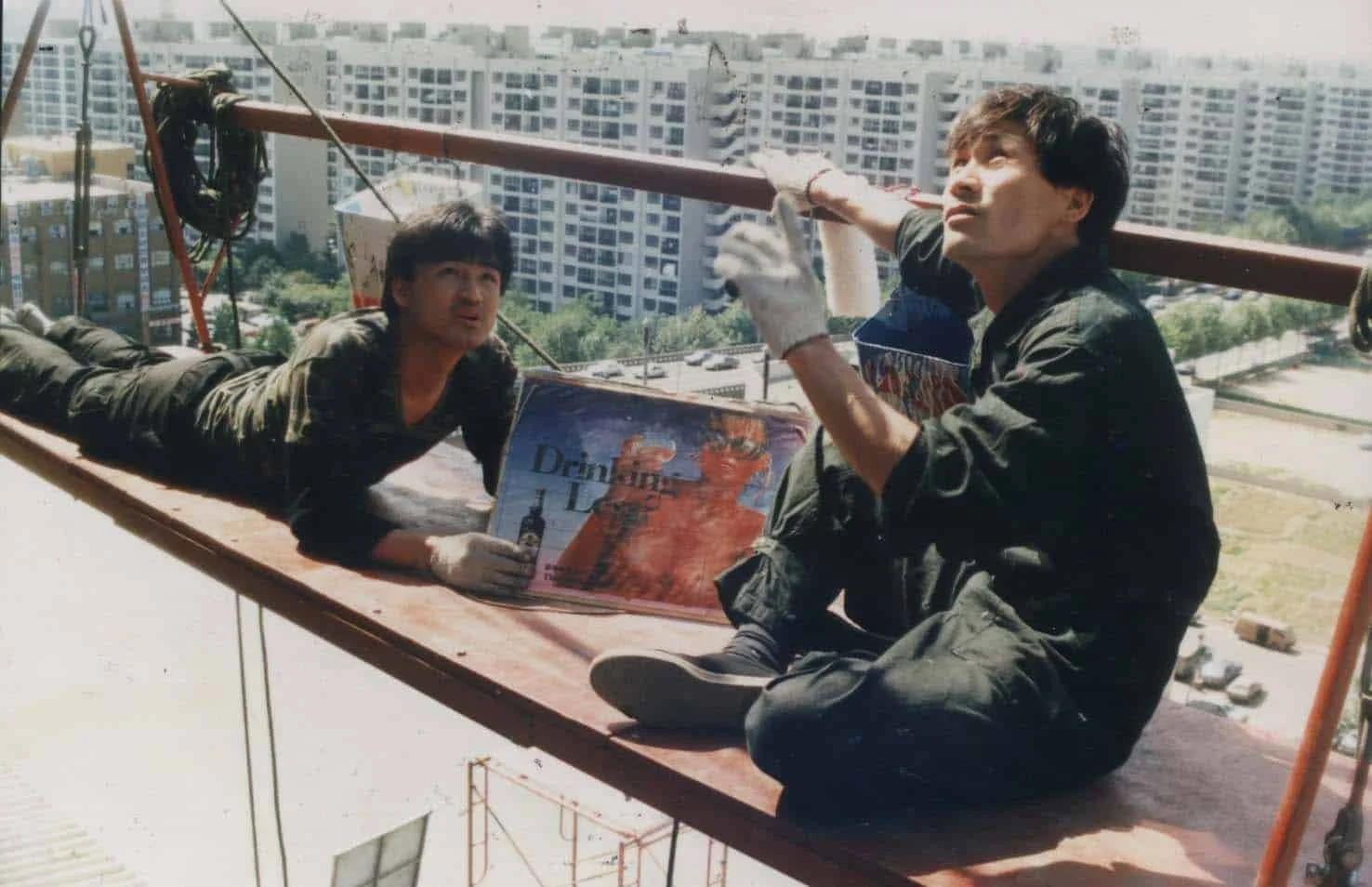

Park Kwang-soo’s debut, Chilsu and Mansu (1988), is a similar take on displaying the lives of the ordinary through the medium of film. It largely explores class disparity, though in a much more subtle way than Bong Joon-ho’s 2019 global box-office smasher, Parasite. In an era when the majority of films produced in Korea had no choice but to seem pro-government, Chilsu and Mansu was unconventionally brave. Laced with scathing irony, the film follows Chilsu and Mansu, two blue-collar workers with few chances for social mobility, as they scrape by earning little money as industrial painters in the glitzy Gangnam neighbourhood. They work in shoddy uniforms against a backdrop of newly built department stores, Burger Kings, and Rick Astley tracks. It’s 1988, the year of the Seoul Olympics, and while some of the city’s population is enjoying Korea’s economic revival, the rest is held down in poverty.

The two men are visibly fed up and frustrated with their end of the stick. Feeling most free when on the rooftops of towering skyscrapers where they work, they stand atop one of their signs and yell out obscenities directed at the young, rich, and privileged people of the area. A crowd draws, unable to hear what the men are shouting, and falsely assume they’re planning to jump. As the scene escalates, news crews, emergency services, and even the army show up. The scene is a perfect allegory for the lack of attention the privileged pay to the plight of the less fortunate. The two men cannot make themselves heard in this society, even when shouting at the top of their lungs. The film is equally critical as it is mocking of the deafness of the upper echelons of society and their eagerness to partake in a post-war copycat American society.

Chilsu and Mansu (1988)

Chilsu and Mansu did not stand alone as a social commentary film. Genre cinema ridiculing modern society and powers within Korea was widespread in the New Wave. Lee Chang-dong’s Peppermint Candy (1999) tells the story of a suicidal man in reverse chronology. The film opens with Young-ho, the middle-aged common person, heading as fast as he can towards an oncoming train. The events in his life that have brought him to this point are inextricably linked to the previous 20 years of social changes and economic fluctuations in Korea. His sense of self is frazzled and worn after living through some of Korea’s most notable moments in history—the dictatorships, student protests, and the IMF crisis. Not to mention his own self-inflicted pain and the hurt he’s caused to the people around him. The once-hushed reality of the everyman is bleakly laid out for us to observe. Peppermint Candy force-feeds its audience a harsh truth about life in Korea for many at the time, a contrast to the pride and glory of the economic boom and modernisation of the country.

Peppermint Candy (1999)

Sociopolitical commentaries even penetrated the world of box office action thrillers, a genre that became a lucrative cash flow in Korea in the 1990s. The arrival of action thrillers was primarily down to the influence of American culture, but films like Shiri (1999) and Tube (2003) proved that Korea could produce its own high-quality, high-grossing action movies. After Bong Joon-ho released Memories of Murder (2003), both Korean and international film fans were anticipating his next work. When his film The Host was released in 2006, it quickly became Korea’s biggest box office hit on record. Internationally, it was labelled, “the best monster movie since Jaws.”

Looking back on The Host in the contemporary context adds to its sinister nature. It’s far from a run-of-the-mill monster movie with an obvious monster villain. Bong’s movie does have a real monster that lurks in the Han river, but The Host’s antagonist is far more multi-dimensional, as is a pattern in his work. The film was inspired by a real case in 2000 when a US morgue official was accused of allowing hazardous chemicals to be deposited in the Han River. The film opens with an American scientist ordering a lower-ranking Korean scientist to pour out an unsafe amount of formaldehyde down the lab drains. First, strange ‘fish’ are spotted, and eventually a huge beast is unveiled. The US military overtakes Seoul, and everyone is forced into quarantine and lockdown. The familiarity is chilling.

Parasite (2019)

The Host is a sharp critique of the lingering US military presence in Korea, smartly packaged in two hours of action-packed monster mayhem. It can also be understood as a criticism of how the Korean government attached itself to the US in the 1990s. The South Korean government officials in the film are portrayed as ineffective and apathetic, while the American officials hold the most power throughout the story. Seoul is depicted as a city suffering under the shadow of American influence, not always known to the people living there. The Host also plays as an eerie foreshadowing of sorts to Bong’s globally-loved hit Parasite, which can be seen as a result of the unresolved issues present in The Host.

Transformations in law and society over the 1980s and 90s allowed Korean cinema to finally reflect the socio-political realities of the time and become a vessel for criticism of the government and state issues. Politically charged cinema had existed throughout the 1900s in Korea but was pointedly pro-government due to censorship laws. The early strict censorship of Korean cinema that confined free speech within the boundaries of the governments’ prerogatives provided something to react against, affording films a new position in society. Filmmakers capitalised on their newly found freedom and produced films accurately addressing social issues, creating Korean cinema’s New Wave.