100 years of Korean cinema: part one - Japanese occupation to the 60s.

Written by Ella Kaill (@ellakaill)

South Korea's popularity around the globe has grown dramatically in the 21st century thanks to its music, TV and food exports. Now, South Korean cinema has earned its own loyal following due to a number of globally successful pictures, including Old Boy, Okja and, most recently, Parasite. Film buffs may also remember the late 1990s and early 00s as a 'golden age' of Korean cinema, during which many South Korean films were just as popular among East-Asian cinema fans as their Japanese and Chinese competitors.

South Korean films released before the 1990s are often harder to access and enjoy relatively limited space in our collective knowledge of Korean cinema. However, many of these films are exceptional displays of Korean talent. They are accompanied by a rich history that can help us further understand the turbulent process of turning what was once a Confucian kingdom-turned-Japanese annexation into the fast-paced metropolis of modern Korea that we see today. This three-part series will guide you through South Korea's modern history, from the early 20th century to the present day, focusing on developments and setbacks in the cinema world.

We begin at the turn of the 20th century. This era of Korean cinema is significant because of the censorship rules that caged the creativity of filmmakers. In order to understand this era of Korean film history, we must first understand the political landscape in Korea at the time.

Korea was officially colonised by Japanese forces by 1910. Until its liberation in 1945, most government officials were Japanese or pro-Japanese Koreans. The Japanese dissolved the Korean army in 1907, shut down all Korean newspapers and left only the Keijo Daily News and its Korean language edition. They suppressed the circulation of textbooks concerning Korean history and revolutions in other countries, and they prioritised Japanese language education over the Korean language. Korean students could even be punished for speaking Korean in the classroom. Places of work were often guarded by the military police and surrounded by barbed wire to prevent escape. There were even cases of massacres of the workers to protect military secrets inside the factories upon completion.

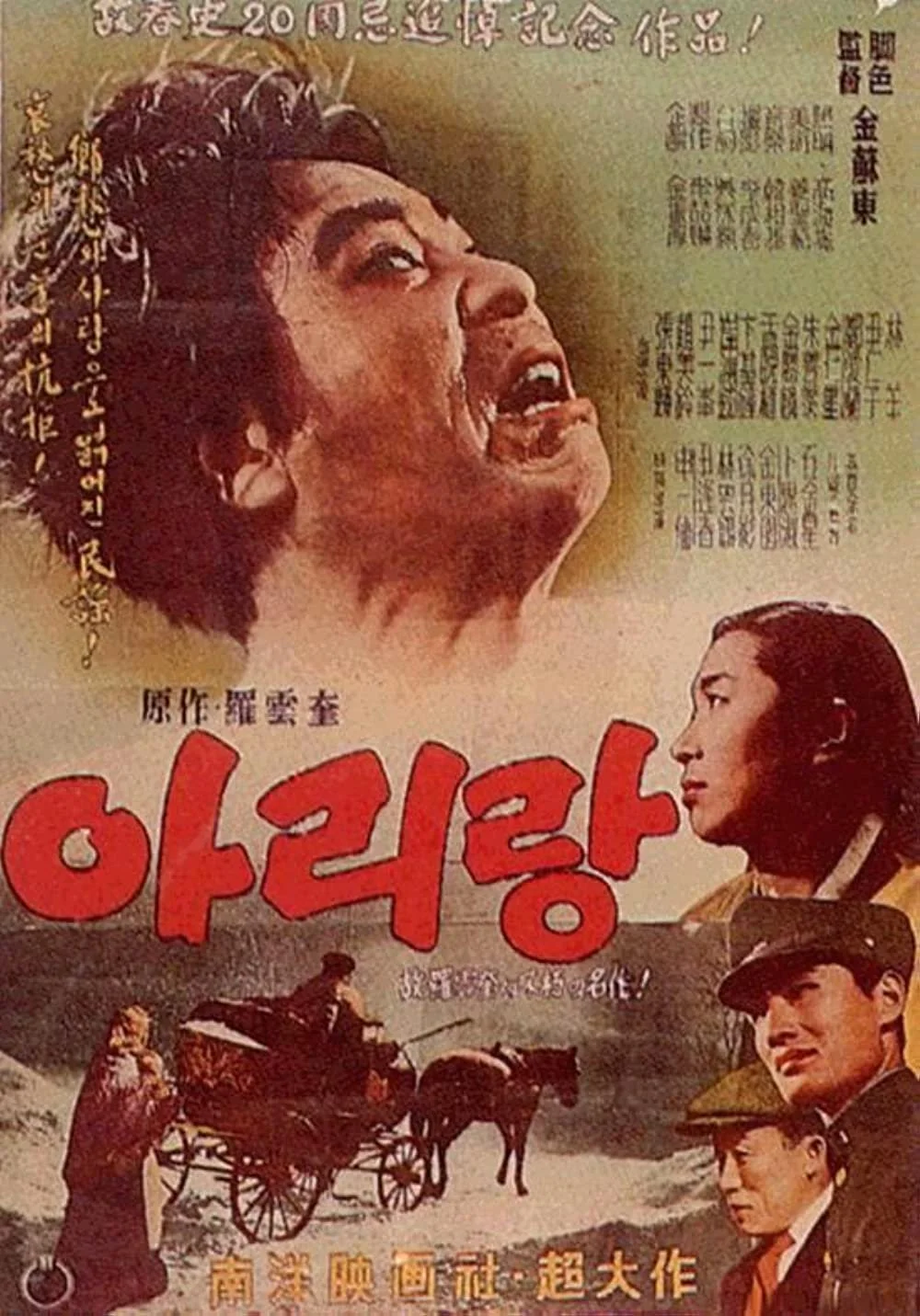

Arirang (1926)

This was a particularly difficult time for women and girls in Korea. Through the 1944 Female Volunteer Corps Service Ordinance, several thousand females between the ages of 12 and 40 were thrown into the workforce, many of whom ended up in munitions factories. Many others were sent to provide sexual services as 'comfort women' to conflict areas in China and other countries where Japanese soldiers were based. Protests by the 'Korean Council for the Women Drafted for Military Sexual Slavery by Japan' continue today every week in front of the Japanese Embassy in Seoul.

Though it may seem hard to believe, Korean filmmakers did emerge during this turbulent start to the 20th century. However, their efforts were plagued by government intervention. Censorship laws that stifled freedom of expression in Korean cinema from the early 20th century towards the 1990s were introduced to make sure no anti-regime content was produced that would have potentially reversed the efforts of the Japanese propaganda. One example of this is Nan Un-Gyu's Arirang (1926) which represented the resentment in Korea against Japanese domination; many parts of his film were cut after Japanese censors realised his intentions. Films were even banned before their release, such as The Underground Village (1931) which depicted the life of those living in poor areas on the outskirts of Seoul. By 1935 Korean filmmakers were forced to make pro-Japanese films, and by 1942 the screening of Korean films was prohibited, and all films were required to be Japanese language. After the Japanese occupation, the American military abolished many laws put in place by the Japanese authorities only to establish different censorship rules in their place, including the Central Motion Picture Exchange, which concerned the importation of American films.

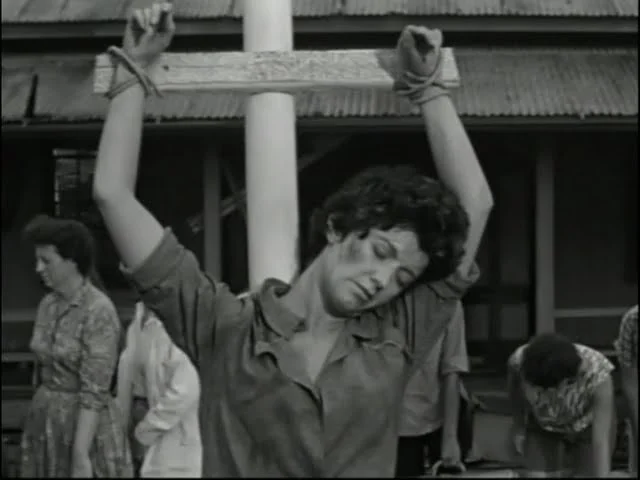

Seven Women Prisoners (1965)

After the liberation from Japanese rule and the Korean war, the Korean film industry was largely inactive. During the mid-1950s, Rhee Syngman, the first President of South Korea, introduced tax exemptions on Korean films to revitalise the industry and make film production easier so that more films would be produced. While this benefited the country's film market and economy, this kind of government intervention in cinema was not widely welcomed by filmmakers. There was a feeling among the cinema world that government intervention in the industry would continue to take away freedom of expression, both during film production and in film reception. Small companies were forced out of business, and the film industry was cornered by a few large companies during this time, just as the government wanted. This marked the beginning of a stagnant film industry in Korea; low-risk genre films took over the screens because they were cheap to produce and quick to put together.

The government also introduced the Grand Bell Awards in 1961 to expand their control over the industry. The awards were a way of stating which films were good enough for recognition, and the government hoped that this would encourage pro-govt, anti-communist films. By 1965 the Quality Film Reward System was also introduced to achieve a similar goal. Well-made films quickly returned to screens, including many anti-communist films, but they were mainly produced to fill the quota and were not the artistic pursuits of the directors. The government continued to control the film industry, and the creativity of filmmakers suffered as a consequence.

Seven Women Prisoners (1965)

Lee Man-hee's Seven Women Prisoners (1965) is an important example of the government's authoritarian approach towards the film industry at this time; police confiscated the film, and Lee Man-hee was put on trial for the charge of being pro-communist. The government made an example of Lee Man-hee, using him as a warning to other filmmakers. During this time, the artistic expression of filmmakers was tightly controlled and observed by the state.

Filmmakers in South Korea have never truly found freedom from the shackles of the censorship laws that bound them during the Japanese occupation and the decades that followed. Strict censorship has continued even up until the present day. In 1980, the government cut the most important line from Im Kwon-taek's Pursuit of Death; "We're the victims of the super powers."

These days, censorship of Korean filmmakers is less concerned with anti-government rhetoric. Instead, we see regular attempts to erase LGBTQ relationships from the screen. In 2015, broadcasting company JTBC received a sanction by the Korea Communication Commission for airing a scene that showed two girls kissing. Even more recently, in 2021, SBS cut a kiss scene between two male characters from a TV broadcast of global blockbuster Bohemian Rhapsody. This inspired YouTube duo Mango Couple to start their campaign 'Bohemian Kiss Challenge', encouraging people of all genders and sexuality to post videos or photos on social media of themselves kissing with hashtags such as #All_Kisses_Are_Equal.

As Korean cinema continues to draw fans from other countries and stand tall next to Western contenders in international film festivals, one wonders if government censorship of domestic and foreign films and TV may become an even more sensitive issue in the future. There may be a disconnect between what draws in foreign audiences and the Korean government's tolerance, which may ultimately lead to international audiences turning their back on the work of talented Korean filmmakers.